This post is a sequel to a previous post on MPs’ degrees

In June, Subtle Engine posted a chart that showed which subject areas were studied by a sample of MPs while at university. A few people suggested that it would also be interesting to see what fields of knowledge the Lords were most comfortable with. So here we go…

TL;DR – Like MPs, members of the Lords primarily studied degrees in arts rather than science or technology subject areas. About 17% of Lords studied STEM subjects (more than MPs’ 13%).

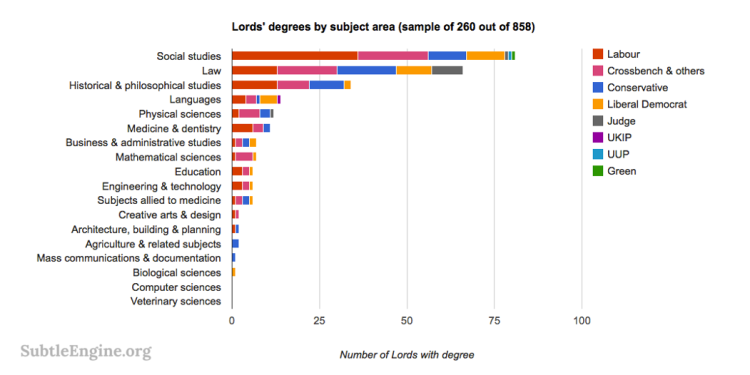

Data collected by a script that looks up each Lord’s Wikipedia entry (click for full size image)

As with MPs, data on Lords’ degrees isn’t published. The approach used in this post (and the previous) is to use an automatic script that looks up Lords’ entries in Wikipedia, and searches for phrases that mention HE qualifications, e.g. “gained a first in…” or “graduated in…”.

Using a list of 858 current Members of the Lords (from They Work For You), the script found Wikipedia entries for at least 636 Lords. Of the 636 entries it was possible to find references to and categorise 260 Lords’ degrees (about 30% of the House) into subject areas.

The four most common subject areas (accounting for 75% of the sample) were identical to those of MPs – Social studies, Law, Historical & philosophical studies and Languages. Again, as with the MPs, there was a fairly rapid drop to the less popular subjects.

About 17% of the sample studied subject areas generally thought of as STEM; slightly higher than the sample of MPs, of which 13% studied STEM subjects. The most popular STEM subject area was physical sciences, followed by Medicine & dentistry and Mathematical sciences.

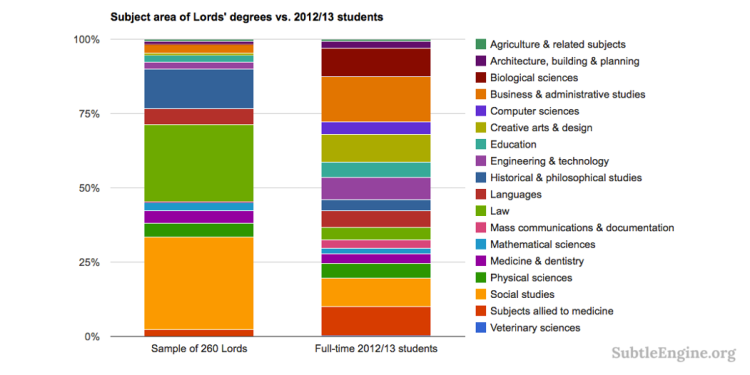

Comparing the Lords’ subject areas to those of the population of students at UK universities in 2012/13 shows the bias towards Social studies, Law and Historical and philosophical studies – and away from others, such as Creative arts and design, or Biological sciences:

As with the previous blog post on MPs’ degrees, the point of this post isn’t that non-STEM degrees aren’t valuable, but that there is a noticeable lack of representatives in the Lords who have studied science and technology subjects at university.

At the risk of jumping on the bandwagon, there’s no better illustration of the need for Lords who are informed of technology than the recent story of Lady O’Cathain (whose Wikipedia article doesn’t mention her degree) and her horror at the discovery of Google Maps:

I was horrified the other day when I was giving a certain website to look at. I could see the roses in my garden. It was on a Google map or something, and I have no idea how it was taken.

Lady O’Cathain joined a new committee called Digital Skills, appointed in June to “examine what [rapidly changing technology] means for the labour market”. Perhaps the Lords should start with themselves?

Note on the script and sample

It’s slightly harder to automatically look up Lords than MPs on Wikipedia, as the URLs of their articles are more colourful. It’s generally easy for a script to find an MP’s Wiki page by concatenating their first and last name (sometimes appending _(politician)):

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Cameron

(Hereditary) Lords are referred to by their title, like The Marquess of Salisbury, but searching for this on Wikipedia results in the page for the title rather than the current holder of that title (searching for the bishops results in a similar issue):

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marquess_of_Salisbury

What we want for our purpose is to find the incumbent’s page, but there’s no consistent way of linking from the title’s page to the current holder (some pages do, and some pages don’t). Here’s the page we actually want for the Marquess of Salisbury:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Gascoyne-Cecil,_7th_Marquess_of_Salisbury

This is by way of an aside, but is mentioned to show that the initial sample of 636 Lords is probably biased towards life peers (who, like MPs, have less ambiguous Wikipedia URLs) and away from hereditary peers and the lords spiritual.

As with the previous post, these charts will not be perfectly accurate, but should show the broad trend fairly reliably. They depend on correct Wikipedia entries as well as the script’s ability to correctly categorise degrees into subject areas.